To keep up to date with more articles like this, subscribe to John’s newsletter.

Anniversaries present us with opportunities – opportunities to celebrate, to contemplate the passage of time and to reflect. This month we’ve seen two pretty significant anniversaries – the terror attacks of 9/11 (now 17 years ago!) and the bankruptcy of global investment bank, Lehman Brothers, just ten short years ago on September 15. Unlike my 20th wedding anniversary earlier this year, which was definitely a milestone to celebrate, these more recent anniversaries have clearly been more about reflection and contemplation.

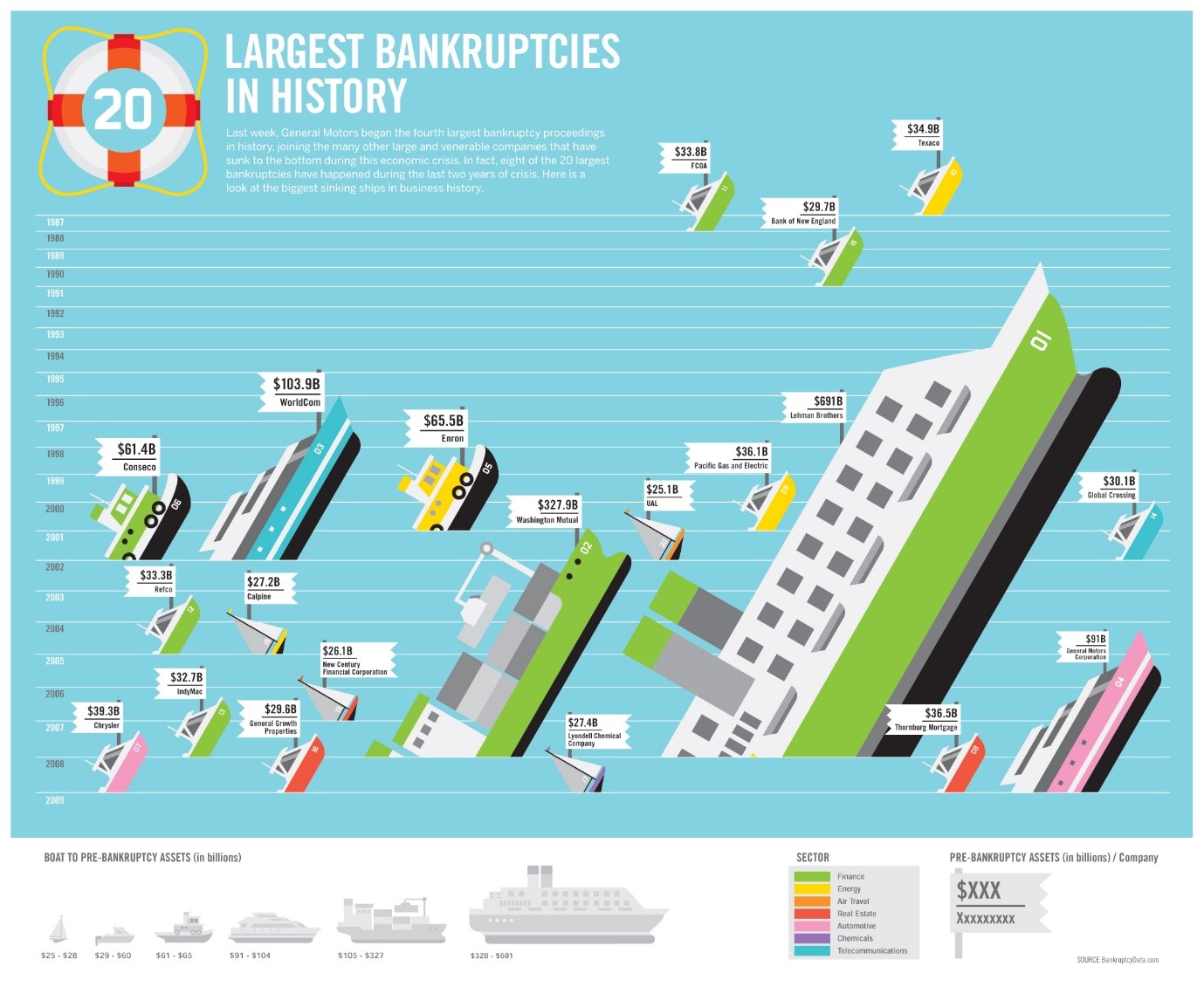

A lot has been written and said in the last week or so about the anniversary of the Lehman Brothers collapse – the largest bankruptcy in history and an event that has come to be regarded as the most significant single event of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). By way of a quick recap, SBS has prepared a simple GFC timeline.

What happened?

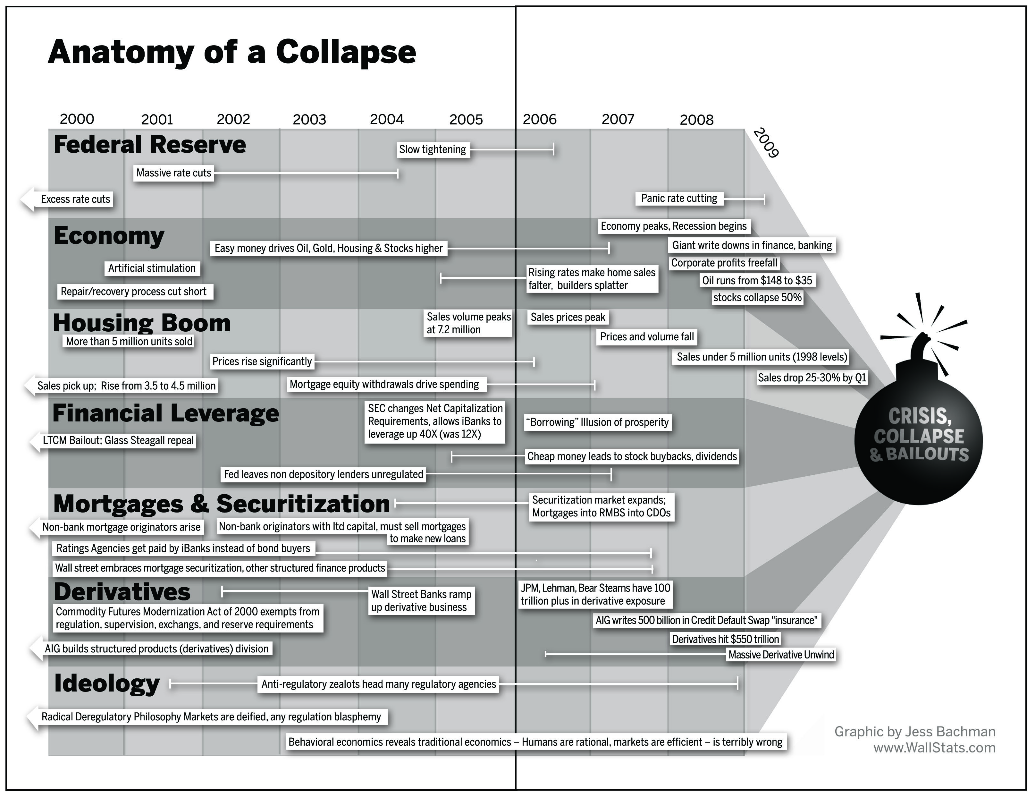

Whilst global financial markets are insanely complex from many perspectives, there is also a significant amount of common sense and simplicity embedded in their practices, behaviour and outcomes over time. Considering markets at their most fundamental, they simply represent a balance (at any particular point in time) of the competing human emotions of greed and fear. It was these emotions – first greed, then fear – combined with a level of regulatory failure (particularly in the US) which fueled much of the bubble and almost all of the crash. The best primer I’ve found of the whole house-of-cards is this eight-minute YouTube video – the crisis of credit visualised. If you want to learn a little more about collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), credit-default-swaps, sub-prime lending or moral hazard, you might enjoy it. The RBA’s summary is also a good place to learn a little more about the underlying causes of the crisis. Or for those on a tight-timeframe, the infographic below by Barry Ritholtz sums it up pretty well too.

Ten years on…

It was easy to believe, at the time, that it was the end of the global economy as we knew it. You may recall that some pretty serious people were so worried about the future of the global economy that they were storing gold bullion in their homes! In fact, it seemed at the time that the closer you were to ground-zero, the deeper the abyss appeared. I spoke with clients at the time who were genuinely worried that their assets, accumulated over a lifetime, would end up (literally) worthless. Caught up in the fear, the media (as they do) fanned the flames, asking questions such as ‘can markets ever recover?’ and making statements like ‘there’s no end in sight!’ as global investment markets plummeted.

But, the world didn’t end.

Markets recovered.

In fact, well-diversified investors, with sensible levels of cash leading into the GFC, now have stronger balance sheets than they did ten years ago (and they’ve enjoyed ten years of income from those portfolios across that period). It seems that financial markets and the global economy are generally more resilient than we give them credit for. Collectively, our optimism and drive to work hard, deliver results, innovate, collaborate and succeed promotes growth and drives the economy forward. Whilst the world is not without risk (on many, many levels) today, the global economy not only recovered, but it is much healthier today than it was in 2008.

But, history, common sense, economic theory and behavioural psychology (in particular) tell us one thing – markets will always cycle. Good regulation can reduce the depth of the crashes, but booms and busts are inevitable – and will remain so as long as fear and greed are human emotions.

So what can investors do?

Accepting the facts is a great place to start.

For most of us, the facts are: to invest is to take risk (in fact, without ‘risk’ there can be no investing at all – it’s fundamental to the equation working out). Risk means ‘not knowing’ – not knowing the future; not knowing when markets will turn; not knowing when the next recession will be (it’s worth noting that we haven’t had a recession in Australia since 1991 – which means anyone younger than 40 has no memory of a recession). “Not knowing” makes it essential to plan for a range of scenarios.

Lesson 1: Cash is king

One of the ways investors can ‘plan’ for the future is by ensuring sufficient levels of cash in their portfolio. Adequate cash in a portfolio provides both a buffer from asset devaluations (minimising the possibility of selling to lock in a loss at the worst possible time) whilst at the same time, providing a means to take advantage of ‘buying opportunities’ when they arise.

Lesson 2: Remember risk (and diversification)

As John Lancaster writes in After the Fall (an excellent, but longer, read in the London Review of Books if you have the chance), “it is an iron law of investment that risks are correlated with returns. The only way you can earn more is by risking more.” While it can be tempting to jump on the bandwagon of the latest investment trend (think Bitcoin perhaps) promising big returns, don’t forget to weigh in the risk involved. And importantly, remember that by selectively combining investments with varying risk and return expectations, you can, in fact, produce a portfolio with a more attractive risk/return profile than any single investment can provide – this is portfolio magic of diversification.

Lesson 3: Your why

Investing is about your goals and objectives. Yet far too many of us act as though it’s about beating some arbitrary benchmark – or even worse, ‘out-performing’ your neighbour, work colleague or brother-in-law. Remember that in hindsight, you can only see the return – rather than the risk. When you understand what’s truly important to you – investing actually becomes easier. You’ll be less likely to be caught up in short-term performance comparisons. You’ll be less likely to second guess your decisions and you’ll be significantly less likely to beat yourself when you get less than 100% of those decisions ‘correct’.

Lesson 4: Understand and manage your emotions

Be aware of your emotions and how they influence your decisions.

My biggest regret from 2008 is the client I wasn’t able to save from his emotions. We had several conversations over a period of a few weeks in late 2008 about his portfolio, the markets and what we saw unfolding during the height of the GFC. He wanted to sell his entire portfolio and sit in cash. His plan was to wait for the crash to pass, with a view to buying back in when the market looked more attractive. This particular client held a sensibly diversified portfolio (that protected him from the worst of the fall), and importantly, he held sufficient cash to fund his planned lifestyle expenses for at least two years (ignoring dividends and earnings). In short, he had no ‘need’ to sell. I also spoke to his wife during the same period – she was just as scared as he was, but she was more aware of the risks of acting on those fears. In the end, he sold out at close to the worst time (although we didn’t know that at the time). Three years later, he hadn’t re-entered the market in any material sense as the combined elements of fear and regret encouraged him to see even more falls over every horizon. With the benefit of hindsight, that single decision has resulted in a relative loss of approximately $600,000.

I think about this (former) client often – how could I have helped him and his wife more? What else could I have done? Ultimately people make their own decisions, but from my perspective, this experience taught me the value of understanding emotions and agreeing on a framework well in advance to assist with managing them.

So, is there another downturn just over the horizon? One way or another a downturn is most certainly on its way – as Shane Oliver puts it in his Cuffelinks article, “History is replete with bubbles and crashes and tells us it’s inevitable as each generation forgets and must relearn the lessons of the past.” But none of us can know exactly when the next crash, correction or crisis is coming or exactly what the trigger may be. Rather than trying to pick the timing, which many prognosticators are currently attempting, the better course is to be prepared for whenever it comes.

And finally, if you’re in the mood for something far more optimistic (and something more worthy of celebration) – in a longer-read format – you could do a lot worse than to pick up one or both of The rational optimist, how prosperity evolves by Matt Ridley or Sapiens, a brief history of humankind by Yuval Noah Harari. These wonderfully readable books powerfully and articulately make the case that human evolution, capitalism, global trade and science have unambiguously improved the lives of billions and have ensured that we all enjoy a standard of living and life expectancy unimagined by prior generations. Optimism, after all, is what drives us to invest!

Disclaimer: This article contains general information only and is not intended to constitute financial product advice. Any information provided or conclusions made, whether express or implied, do not take into account the investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs of an investor. It should not be relied upon as a substitute for professional advice.